|

Landing Craft Gun 13 - LCG 13.

Lucky for Some - A Sick Bay Attendant's Story

Background

In 1941, aged 20, my number came up for

military service. I had a medical examination in Manchester where my light weight

of about eight stone was commented on. I stated a preference for the Navy

as a sick berth attendant and I passed the medical A1. I was then

interviewed by three Naval

Officers who fired general knowledge questions including how to spell

corporation. When I asked, “Did you say co-operation or corporation?” I

sensed I'd passed the test!

My dad, aged 41, was serving as a sick berth

attendant in the Naval Hospital at Haslar near Gosport, Hants. He worried

constantly about the bombing back home, not knowing what was happening to

his family. He eventually had a mental breakdown and was medically discharged with anxiety neurosis. I don’t think he

should have been called for service in the first place. My dad, aged 41, was serving as a sick berth

attendant in the Naval Hospital at Haslar near Gosport, Hants. He worried

constantly about the bombing back home, not knowing what was happening to

his family. He eventually had a mental breakdown and was medically discharged with anxiety neurosis. I don’t think he

should have been called for service in the first place.

[Photo; HMS Collingwood with the author,

Sick Bay Attendant, John Francis Percival top right].

In August 1941, I received orders to report

to HMS Collingwood at Fareham, Hampshire. These were my “calling up

papers” with vague travel instructions, a travel warrant to Euston

station, underground tickets to Waterloo and a warrant to Portsmouth. I

think I was secretly relieved when the time came, since most of my friends

and work mates were already in uniform. It was a lovely sunny day when I

arrived at HMS Collingwood to be greeted at the gate by a

naval guard, who had become an old sweat after his few months training.

There we stood, a band of civilians with our

suitcases, average age about 20. “Right you lot, get fell in over there”,

barked a petty officer. We were split up into sections of thirty. My group

of thirty was introduced to PO Woods, a stocky, red-faced man; with a

smile that made him look human. “Right lads, you’re in the navy now. The

first thing you have to learn is to do as you’re told, pay attention, obey

all orders and we should get on well. You’re in the Fo’c’sle (Forecastle)

Division, hut number 4. The floor is now the deck, the walls the bulkhead, the ceiling the deckhead, the bathrooms the ablutions and the toilets

the heads. You’ll soon get used to it.”

The

wooden hut, which was to be my home for the next three months, was quite

clean and comfortable and was linked to a corridor. The ablutions and

heads were across the corridor. There were double bunk beds and we each

had a locker to be kept tidy at all times. I was in the top bunk of the

end bed next to the corridor. The lad in the bottom bunk came from Bolton,

which wasn't far from my home town of Warrington. He spoke with a soft

Lancashire accent and we became good mates from day one.

On the first night, I wore pyjamas bought for

me by my mum. I think it was the first time in my life I had ever worn

pyjamas and, as events unfolded, I didn’t wear them for long. After lights out at ten

o’clock, our hut was raided by a gang of old sailors from a few huts away,

who had probably been in the Navy all of four weeks. My pyjamas were

ripped off me and a stirrup pump was used to squirt water under the bed clothes. We

had just experienced the initiation ceremony.

They were a mixed bag of lads in the hut

from various parts of the country and soon bonded to form quite a good

team. We were issued with our uniforms and kit. Standing naked in front of a Wren, (yes, a girl),

while being issued with underwear was a challenge as was finding a cap big

enough for my head!.

Anyway I completed the basic training and sick berth attendant training

and was assigned to Landing Craft Gun 13.

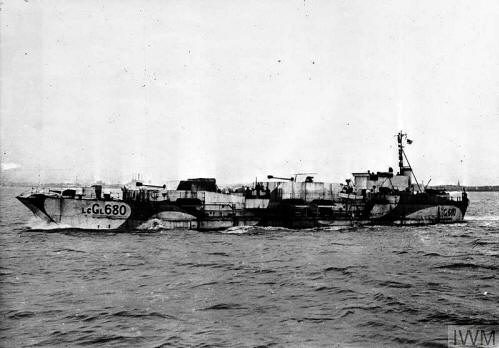

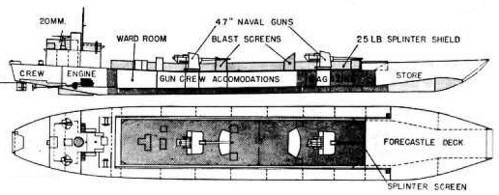

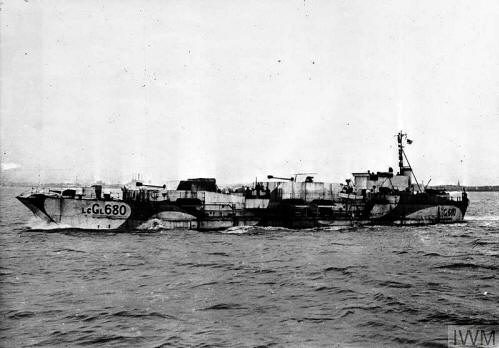

LCG

13

%20PENNANT%20NUMBERS_small.jpg) I found LCG13 moored alongside a jetty

amongst a flotilla of LCGs. They were strange looking craft, numbered in

the sequence 1 to 20, more like a canal barge I'd seen back

home. They were small vessels by Royal Navy standards, shaped like a

coffin, with a square nose instead of the conventional pointed bow. They

had two 4.7 inch (120mm) calibre guns and two anti-aircraft guns. I found LCG13 moored alongside a jetty

amongst a flotilla of LCGs. They were strange looking craft, numbered in

the sequence 1 to 20, more like a canal barge I'd seen back

home. They were small vessels by Royal Navy standards, shaped like a

coffin, with a square nose instead of the conventional pointed bow. They

had two 4.7 inch (120mm) calibre guns and two anti-aircraft guns.

[Thumbnail opposite, click to enlarge; This is an extract from the Admiralty's 'Green List' of

Landing Craft dispositions just prior to D Day. By then the original

allocation of 20 pennant numbers had been used up, the remainder probably

taking on the pennant numbers of the LCTs (Landing Craft Tanks) from which

they were converted to LCGs].

After

negotiating a vertical ladder from the quayside, I was on board my first

ship. The quartermaster greeted me with, “Hello, Doc. Are you joining us?

Report to the skipper in the ward room, down that hatchway in front of the

bridge.”

The skipper was Lieutenant Willoughby

(George to his friends). He was a big chap with a round cheerful face,

twinkling eyes and quite a full beard not unlike a picture I'd seen of

Henry VIII. He was very friendly and rather informal. “Welcome on board. I

don’t know what we're going to do with you. We’ve not had a Sick Berth

Attendant before. I suppose you’ll be known as the Doc.” He offered me a

cigarette, told me to sit down and said, “I don’t know where we’re going

to put you, there's not a lot of space.” The skipper was Lieutenant Willoughby

(George to his friends). He was a big chap with a round cheerful face,

twinkling eyes and quite a full beard not unlike a picture I'd seen of

Henry VIII. He was very friendly and rather informal. “Welcome on board. I

don’t know what we're going to do with you. We’ve not had a Sick Berth

Attendant before. I suppose you’ll be known as the Doc.” He offered me a

cigarette, told me to sit down and said, “I don’t know where we’re going

to put you, there's not a lot of space.”

On board were thirty Royal Marines who

manned the guns, a Corporal and a Sergeant. There were also about twenty

assorted sailors - Able Seamen, Signalmen, Telegraphists, Stokers and

Leading Seamen known as the Coxswain, to man the craft. The Signalmen ran

up the signal flags known as bunting and were known as “bunting tossers”

or “bunts” for short, while the telegraphists were known as “sparks”.

The skipper introduced me to the 1st

Lieutenant, known as “Jimmy the One” and to the Marine Officer, a tall gangling sort of man with a

posh accent. There was no room for me in the Sergeant’s Mess since the

Coxswain, Sergeant and Corporal fully occupied a space measuring only

about 10 feet by 6 feet (3 x 2m) with headroom from the deck to the deck

head of about 7 feet. I opted to sleep in the seaman’s mess deck with the

rest of the lads. At the age of 22, I was one of the oldest onboard and

began to feel a bit important.

I slung my hammock on two spare hooks and

settled down to a good night’s sleep. At about 7 am, the Corporal of

Marines struck the bottom of each hammock with a cane to the refrain

“Wakey wakey, rise and shine. Hands off cocks and on socks.” The commotion

woke me up too when I heard one of the lads say, “Hey, Corp, that’s the

Doc.” The corporal apologised and covered me up to sleep on. I knew I was

going to be okay with these lads.

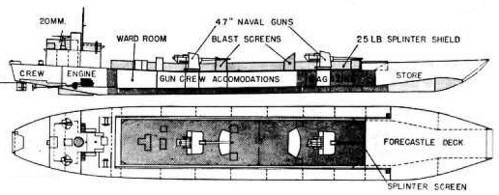

I

dressed in time for breakfast, which comprised a couple of slices of bacon

and some fried powdered egg. The coke burning galley stove was amidships

and provided hot water from a rectangular boiler... sometimes... maybe.

Cold water was drawn by hand pump on the bulkhead beside the stove. The

galley was partitioned from the Marines Mess Deck on the starboard side,

while on the portside were the food stores and a secure area behind a

metal grating where the rum was stored in demijohns. Forward of the

Marines Mess Deck was the ammunition room. There was a passage way

alongside this on the port side with watertight doors fore and aft.

In the fo’c’sle

area, immediately behind the bow, were two toilets or heads with metal

loops secured to the bulkheads each side of the “thrones”. These were to

hold on to, to avoid

becoming dethroned when the weather was rough! There was a passage-way aft

of the Marines Mess Deck ('Gun Crew Accommodations' in diagram opposite) running down the portside, off which was the

Seamen's Mess Deck and further aft was a door off to the ward room. In the fo’c’sle

area, immediately behind the bow, were two toilets or heads with metal

loops secured to the bulkheads each side of the “thrones”. These were to

hold on to, to avoid

becoming dethroned when the weather was rough! There was a passage-way aft

of the Marines Mess Deck ('Gun Crew Accommodations' in diagram opposite) running down the portside, off which was the

Seamen's Mess Deck and further aft was a door off to the ward room.

There

was a watertight hatch on the deck into the Marines Mess Deck alongside

the ammunition room. This allowed “ammo” to be passed onto the deck where

it was needed. There was a watertight hatch for’d of the bridge with a

companionway leading to the wardroom on the portside and two smaller rooms

on the starboard side, one for the 1st Lieutenant and the other for the

Marine Officer.

The Seamen's Mess Deck was quite cramped too

with a circular steel pillar, supporting one of the guns above, in the

middle of the space. On the starboard side, forward of the pillar and

partitioned off, was the Sergeants' Mess. Between the bulkhead of the

Sergeants' Mess and Jimmy the One’s cabin was about an eight-foot space for

the seamen, with a fixed table in the middle. There was also a fixed table

on the portside to the Seamen’s Mess.

There was only about a seven or eight foot

clearance between the deck and the deckhead throughout the craft. Aft, was

the bridge, containing the wheelhouse, which was also my sick bay with my

box containing basic medical supplies. Aft of the wheelhouse on the portside was the skipper's

cabin, and on the starboard side was a small galley with a coke stove for

the officers' meals. On the rear quarterdeck was the capstan for the

anchor and a watertight hatch leading to the engine room.

My duties were to tend to any sick or

injured crew members and marines and to escort them to a doctor, if

required, usually on a nearby large ship. Because I was on call 24/7, further

duties would be arranged on a voluntary basis. I usually undertook look out duties

on the bridge to help with the seamen’s watches.

I had only been on board a couple of days

when I learned a valuable lesson. The corporal was dishing out the sweet

ration known as nutty. He shouted, “Doc, come and get your nutty.” Without

thinking, I put one foot through the doorway and hit my head on the

bulkhead, knocking myself out. I woke up on the wardroom table with the

skipper grinning down on me saying, “You’re supposed to be looking after

us. Don’t make a habit of it.” I had a 2-inch gash on my head.

Leading Seaman Hopkins, known as Hoppy, took

over my care. He and skipper George were on first name terms, as he was

also the Skipper’s steward. One day, I accompanied Hoppy ashore to do a

bit of shopping for George, who cautioned Hoppy, “I think you’ve been doing

a bit of a fiddle with my change. I don’t mind a tanner or a bob (small

change), as long

as you keep it to the minimum.”

While we were ashore, I spotted a Marine

popping his head out of the top floor window of an hotel. His name was

Maxy Bacon, who had been confined to a small room on the top floor as

punishment for going AWOL (absent without leave). When he returned to the

ship, I discovered that Maxy was a bit of a character. He had a pair of

hand operated hair clippers from his civvy days but wouldn’t let anyone

borrow them, since he charged sixpence a time for a haircut, which left

only a fringe at the front.

Operations in the Mediterranean Operations in the Mediterranean

We spent a couple of weeks tied up to the

jetty before we were issued tropical kit - white shorts and

trousers, white jacket and white cap covers. No one knew where we were

going but the buzz was somewhere cold, the tropical kit being to fool any

German spies.

Eventually, we cast off from the

quayside and I looked forward to my first trip to sea. I could feel the

vibration of the engines as we took our place in a convoy in calm seas. I

survived the first day without feeling sick and managed to eat and drink

normally. On the second morning, I lowered myself from my hammock and put

my feet on the deck, which was tilting from side to side and rising and

falling. I tried to ignore the onset of nausea and ate breakfast as usual

with the ever present smell of diesel fumes from the engines hanging in

the air. I went on deck for fresh air and completed an 8am to noon

watch as lookout on the bridge.

[Photo; Future Sick Bay Attendant, John

Francis Percival on the left with his siblings in the 1930s].

In the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean the

waves were ten to twelve feet high (3 to 4m). Typically, a mountain of

water would approach our craft, disappear beneath us to pick us up on the

crest of the wave. Then a crashing fall into a trough, only for the cycle

to be repeated over and over. I fought the feeling of nausea but, when I

came off watch, I was violently sick. I just lay on the deck wearing a

duffle coat with an oilskin on top. Most of the other lads were in the

same condition but carried on as best they could, many clutching a bucket

into which they were sick. It was a thoroughly unpleasant experience, as

yellow, grey and pale green faces testified. I stayed on the open deck and

struggled not to die!

As we cruised along at around 4 to 6 knots,

we received a signal alerting us to German E boat activity in our

vicinity. This took our minds off our seasickness as plans were made in

the event of an attack. Four craft in our flotilla, including LCG 13, were

to engage the enemy, while the rest dispersed at full speed. Our top speed

was ten knots and our craft not very manoeuvrable, while the E boats were

very fast and agile. We imagined our worst fears and the sea sickness eased

off, but a lot of us had diarrhoea with the shock of it all. Just when our

situation looked most desperate a British cruiser and a few destroyers

appeared over the horizon. The panic was over and we could, once again

concentrate on our nausea! Perhaps we should have had more faith, since

each of the craft had an experienced seaman on board, typically a 3 badge

Able Seamen, who had been in service since Nelson was a lad.

One morning around 4am, as I lay on deck

feeling like death, our 'three badger', known as Stripey because of the

three stripes on his arm, gave me a cup of steaming cocoa laced with

rum. I managed to force it down but, whilst it didn’t make me feel better,

it gave me something to throw up. The sea conditions worsened with

mountainous waves which allowed the propellers to race as they came out of

the water, followed by shuddering as the craft crashed down into the next

trough. Eventually, I felt well enough to return to the mess deck, where I

had a good wash and shave. Up in the fo’c’sle things were grim, with

condensation dripping off the deck head forming pools of rusty water and

the heads smelly despite the disinfectant. In all, I must have been

sick for about 7 days.

Due

to poor storage conditions our supply of bread soon became mouldy, so we nibbled

on ship’s biscuits, known as hard tack. Soya sausage links, which tasted

like vulcanised rubber and herrings in tomato sauce had been thrown

overboard. Due

to poor storage conditions our supply of bread soon became mouldy, so we nibbled

on ship’s biscuits, known as hard tack. Soya sausage links, which tasted

like vulcanised rubber and herrings in tomato sauce had been thrown

overboard.

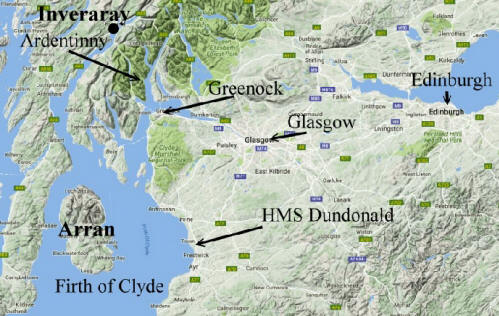

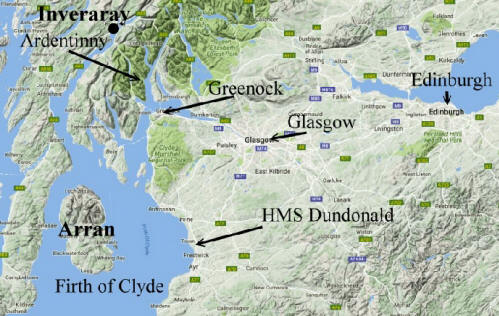

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

After about nine days, we reached our first

port of call, Gibraltar. This was a more vibrant world than the one we had left

behind in the UK, with brightly lit cafes and bars and street lights. At

the first opportunity, Hoppy set off to purchase bread with the help of a

reluctant Spanish lorry driver he had persuaded to help at the point of an

unloaded German Luger pistol... or so the story goes.

Every so often, we could hear a loud ping

resonating through the craft, which was caused by small depth charges, dropped at

regular intervals, to deter German divers from attaching magnetic limpet

mines to the sides of our ships.

We were in Gibraltar for about a week, by

which time everyone had fully recovered from seasickness. When we sailed

from Gibraltar one morning in thick mist, skipper George lost visual

contact with the flotilla and speeded up to catch them. When the mist

cleared he dropped anchor to consider his options. We were in the calm

waters of the Med and could see a small island on our port side. From our

stern, our flotilla came into view with a terse Aldiss lamp message from

our flag ship, "Where the hell have you been? We all slowed down

thinking you were behind us." Our skipper replied, “I thought you were

ahead of us, so I speeded up to catch you but I was pulling away from

you.” The Flag ship replied, “Keep closer formation in future and keep in

contact with the nearest craft.”

We

had no idea of our destination until we all arrived safely in the French

Algerian port of Djidjelli. There was a rocky causeway jutting out to sea,

forming a natural harbour. All the buildings were white and the temperature was

about 90° Fahrenheit (32c) in the shade. We dressed in the white tropical rig we

had been issued with at Falmouth - shorts by day and, as this was malaria

country, long trousers in the evening.

There was a local market, where we could buy

supplies. The bread, shaped like a French loaf, had a vinegary taste, but

fresh bread was a luxury. The Arabs sat on the pavement with dormant

chickens for sale. On agreeing a price after a bit of haggling, the Arab

lifted the chicken's head from under its wing to wake it up. With the

chicken on board, we had to kill it. A couple of dozen big, strong Marine

Commandos had no heart to perform the execution. A tall AB called Lofty, a

Devonshire man with farming experience, came to the rescue, grabbed the

chicken by the head and threw the body to break its neck. His over

exuberant action left him with the chicken's head in his hand, while the

headless chicken went over the side flapping about in the water. The next

challenge was to fire up the galley stove to provide enough heat to cook

it.

We were constantly pestered by young Arab

lads selling goods and services. “You want shoe shine Johnny? Me got

Cherry Blossom, very good” or “You want eggs?” or “You want jig jig Johnny?

Me got big sister, plenty jig jig very good”. We soon learned the Arabian

word for “bugger off” was “imshee”, which usually ended the conversation.

Watermelons were the most popular product in the market, because the ship's water

was lukewarm and chlorinated. The

melon was cold, very refreshing and relatively cheap, until the Yanks

arrived, when the price trebled.

There was a hospital up on a hill where Sick

Berth Attendants from our flotilla helped out in shifts. As we passed

through the Arab quarters to get there, resplendent in our white uniforms

with the red cross on our arms, locals would make way for us deferentially

bowing as they muttered “Le croix rouge.” The free clinic we provided

twice a week was no doubt the cause of their reverence. While in the

hospital I slept on the first floor, a large room with a tiled floor and a

window space without windows. I put the mattress from my hammock on the

deck and rigged a mosquito net over it. I treated a lot of mosquito bites,

some of which became infected in hot climate and were slow to heal, while

others suffered from malaria, dysentery, sand fly fever and the

consequences of succumbing to the favours of the Arab lads’ big

sisters!

Back on board I was issued with mepachrine

tablets for malaria, anti-mosquito paste and lime juice. However, a lot of

the lads weren’t swallowing their tablets or drinking their lime juice so,

forming in line, the Sergeant opened their mouths, the Corporal popped in

the pill and closed their mouths making sure they’d swallowed them. The

Coxswain followed behind me with the lime juice, which was not sweetened.

This had the effect of sucking in the cheeks making the mouth like a beak

and if they’d been on perches they’d have looked like a row of budgies. It

was, nonetheless, important for them to take these preventatives. Back on board I was issued with mepachrine

tablets for malaria, anti-mosquito paste and lime juice. However, a lot of

the lads weren’t swallowing their tablets or drinking their lime juice so,

forming in line, the Sergeant opened their mouths, the Corporal popped in

the pill and closed their mouths making sure they’d swallowed them. The

Coxswain followed behind me with the lime juice, which was not sweetened.

This had the effect of sucking in the cheeks making the mouth like a beak

and if they’d been on perches they’d have looked like a row of budgies. It

was, nonetheless, important for them to take these preventatives.

Fresh water had to be used sparingly, so we

were issued with sea water soap, which, when mixed with the sweat on your

body, produced sticky black streaks. It was quite effective when buckets

of sea water were used to wash you down. The deck was too hot to walk on

unprotected during the day.

While still in Djidjelli, one night at about

two o’clock, I was wakened up by an engineer officer who had just joined

the ship. “Sorry to wake you Doc”, he said, with a drunken slur in his

voice. “Old George has fallen and hurt his leg.” The ship was in

darkness, as the generator was switched off. With the aid of a battery

powered lamp, he led me down the passageway on the port side through the

wardroom. “Bugger George for a minute", he said, "let’s find his whisky

bottle and have a drink.” That done, we found George in his cabin aft, next

to the wheelhouse where I kept my medicine chest. George had quite a gash

on his shin, which I cleaned up and bandaged. He thanked me and suggested

the engineer officer and I should have a drink. “Thanks George, where do

you keep your whisky?” asked the engineer officer, knowing full well it was

where they had let it. We sat chatting until we’d finished the

bottle! The engineer officer was an interesting chap. He was a dirt track

rider in Civvy Street from Birmingham and was known as “Brummy”.

We did quite a bit of swimming from a

silvery sandy beach with clear blue water near Djidjelli but not

altogether safe. Many of the men picked up little black thorns in the

soles of their feet, which were very hard to remove. I found it best to

leave them in place, since they would come up rather like blackheads in a

few days. A hot soak and they could easily be squeezed out with a spurt of

pus. They were caused by some marine life that buried itself in the sand,

so gym shoes had to be worn when bathing.

After a couple of weeks, we left Djidjelli

for Valetta harbour in Malta in calm blue seas and very hot sunshine. Most

of the buildings in Malta were white to reflect the heat of the sun and

there was a lot of evidence of the severe bombings the locals had endured.

Convoys with supplies and fuel were now arriving safely and bars and cafes

were open. We heard the Naval Club, possibly called Union Jack Club, had

taken a delivery of beer. This proved to be correct but they had no

glasses. Ever inventive, the soldiers found a unique way of making their

own glasses by filling bottles with oil to just over half full and

sticking a red hot poker through the neck which caused a clean break at

the level of the oil. I thoroughly cleaned an empty tin under a cold water

tap, dried it off on my handkerchief and then, sheer bliss, quaffing my

thirst with my first decent drink since Falmouth.

The harbour was full of landing craft of

many types and, after about a week, we all set sail for Cape Bonn in North

Africa, where we took on stores, water and fuel. We then mustered off Sfax

and laid at anchor, still not knowing what our next objective was. We swam

quite often in the knowledge that there was a dangerous, fast current.

When we dived off the fo’c’sle, we curled our hands to steer straight back

to the ship. It was now nearing the end of May 1943.

Sicily

and Italy

Our

invasion flotilla comprised at least one hundred craft as we set sail for

Sicily. As we approached the island on the night of the 9th of July, a storm

blew up causing rough sea conditions. I was relieved not to be sick. We were

towing a small LCP (Landing Craft Personnel) carrying an Army wireless crew, who

were all very sick. We hauled them in to welcome them on board the comparative

comfort of our larger craft. Our

invasion flotilla comprised at least one hundred craft as we set sail for

Sicily. As we approached the island on the night of the 9th of July, a storm

blew up causing rough sea conditions. I was relieved not to be sick. We were

towing a small LCP (Landing Craft Personnel) carrying an Army wireless crew, who

were all very sick. We hauled them in to welcome them on board the comparative

comfort of our larger craft.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

We landed on the south eastern corner of Sicily and

the marines fired our guns in anger for the first time, aiming at buildings

along the beach and shore line to clear the way for the troops to land. We

received a sarcastic message saying, “Congratulations, you have killed two fish

and probably wounded a few more.” The marines adjusted their sights and, soon

after, white flags of surrender appeared from the buildings ashore. Our next

targets, not visible to us, were provided by a Forward Observation Officer (FOO),

who was close to the front line. A few retaliatory shells exploded harmlessly in

the water nearby. The Germans, anticipating a landing on Greece, were not

waiting for us, hence a comparatively easy first strike on Sicily.

We moved northwards up the east coast of the

island, supporting the advancing army with our close inshore fire power,

first past Syracuse and then Augusta where we encountered a few air raids.

An ammunition lighter was hit, exploded and immediately sank, leaving a few

bodies floating in the water. Augusta harbour was a former Italian air arm

base, now in our hands. We dropped anchor, went ashore and deprived an

Italian naval store of all kinds of kit. Unbeknown to us, we were being

watched by a newly appointed harbour master who signalled, “You have one

hour to return what you have taken” and reminded us that the penalty for

looting was death. We had it all back in the store in half an hour!

Mount

Etna was a few miles inland and since there were plenty of vineyards

around we were soon bartering corned beef or soap in exchange for vino

- Muscatel. We ran out of bread but a cruiser, anchored in the

harbour, offered to help, so we tied up alongside. Four of us were in

the wheelhouse as we looked forward to a great feast of soya links and

bread. We took off the craft's wheel and made a table of it when an

air raid warning sounded. The cruiser cast us off, upped anchor and

began to move to avoid becoming a sitting target. Mount

Etna was a few miles inland and since there were plenty of vineyards

around we were soon bartering corned beef or soap in exchange for vino

- Muscatel. We ran out of bread but a cruiser, anchored in the

harbour, offered to help, so we tied up alongside. Four of us were in

the wheelhouse as we looked forward to a great feast of soya links and

bread. We took off the craft's wheel and made a table of it when an

air raid warning sounded. The cruiser cast us off, upped anchor and

began to move to avoid becoming a sitting target.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

Our skipper, who was on our bridge, bellowed

down the voice pipe, “Start engines”. The reply was “Engines started, sir”.

The skipper then ordered “Full ahead both”. The reply was “Both engines

full ahead, sir”. The skipper ordered, “Wheel hard to starboard” There was a

pause and then the immortal words “Just a minute, sir, we have to screw

the wheel back on.” The language that followed cannot be repeated here!

Around this time they began to swap the sick

bay staff about. I joined LCG10, LCG12 and finally LCG9. We were still

based in Augusta harbour, taking turns up the coast firing at targets

given by the Forward Observation Officer. On one of these operations we

were spotted by a German plane while quite close to shore. I doubt the

Germans realised such a small barge could carry such big guns. We had a

near miss, which lifted our stern out of the water, smashing most of the

few dishes on board. Thankfully, we received a signal form a destroyer near the horizon, “Get

the hell out of there”. So we did.

On board, back in the harbour, further drama

occurred. The marines had picked up quite a few Italian rifles and

ammunition. One of them inexplicably put a couple of bullets in the galley

stove and when they didn't explode straight away, he lifted the circular

lid on top of the stove at the very moment they did explode. He got a

small piece of shrapnel in his eye, and on the instruction of a doctor on

shore, I accompanied the marine to a field hospital in Syracuse. We went

in an ambulance and when I came out of the hospital having delivered the

patient, the ambulance driver said he was not going back to Augusta, I

would have to thumb a lift.

An army lorry pulled up and I joined some

unguarded Italian prisoners in the back of it. I decided to half sit on

the cab so I could face them all. When I pulled out my pipe and tobacco

pouch, immediately about twenty fag papers were thrust in my direction.

When they all had their fags, they started chattering in broken English

and that's when I learned that Catania had surrendered. They were all quite cheerful,

except when the lorry suddenly braked due to a sneak air attack. The

Italians were in the ditch before we came to a full stop. We got back to

Augusta and unloaded the prisoners. The Italians were giving themselves up

in droves at this point.

After a week or two, we moved up the coast

and finally arrived at Messina, where we anchored in the straits between

Sicily and the Italian mainland. The capture of Sicily was now complete.

The armies mustered around Messina and along the straits in preparation

for landing on the mainland. One night all hell let loose with a terrific

barrage of gunfire from the army and all the 4.7 guns of the LCGs. By dawn

there were white flags everywhere along the toe of the Italian mainland.

We dropped anchor and relaxed for a while, but in the middle of the

afternoon without any warning, there were a few explosions and spurts of

water too close for comfort, indicating that German mortars and 88 guns had

found our range. We opened fire in the hope of hitting something. Whether

or not we were successful, I don’t know. We upped anchor and moved away.

While ashore in Messina, a Sicilian civilian

wondered what the hell our strange looking craft was and how we managed to

live on such a thing. He spoke good English and did not like the Americans

much. He said, ”The British, they build a de ship, they put on a de guns

and armament and then try to find a place for de men. Americano build a de

ship, make a de good place for de crew, good kitchens, plenty food,

fridges, canteens, etc., then wonder where to put a de guns.” He

continued, “British planes drop a de bombs, German he duck, German drop a

de bomb, British he duck. Americano drop a de bomb, everybody duck!” A

good navy yarn.

The next landing was at Vibo Valentia (Vibo

Marina?), a small Italian harbour behind enemy lines on the west coast of

the toe of Italy. The LCIs, LSTs, LCAs (Landing craft Infantry, Tank and

Assault) and other small craft were taking a pounding from German 88 mm

guns, when a LCG and LCF (Flak) engaged the enemy. LCG12 opened up with

her two 4.7 guns firing at the German 88 mm guns and the LCF4 sprayed the

German machine gun positions with rapid fire. The German gunners then

concentrated their fire on LCG12, but she stood fast, carried on firing

for over half an hour, allowing most of our landing craft to escape from

the harbour; but then she was hit, probably by an anti-personnel shell

which hit the yardarm above the bridge, killing all of the officers and a

lot of the crew. Ordinary seaman T H Hill took the craft out to safety.

His action saved the craft and the remaining crew and their guns. The 15"

guns of HMS Erebus finally silenced the Germans.

It was quite a shock to me to hear of the

LCG12 casualties. I had been on board her for a short period when they

swapped us about in Augusta and had got to know most of the crew. I heard

one lad I only knew as Ginger had died as he had lived, sat over a

bucketful of dobheying when he had the top of his head taken off.

Return to

Blighty

Our LCTs and LCGs returned to Messina where

orders were received for 9 LCGs to proceed to Malta and then back to the

UK. I was then on board LCG 9 at the time which was included in these

arrangements. On a recount of the numbers, no one knew where LCGs 15 and

16 were, or even if they still existed.

We enjoyed a few days of rest and

recuperation in Malta and, as usual, were pestered by locals in small boats.

They were

rather like gondolas, called ‘disaus’ and were propelled by skulling with one oar.

They were interested in "gash", which was anything we were throwing away.

It was rumoured that buckets of waste food were sorted, cleaned up,

re-cooked and served to an unsuspecting public!

There was a street in Valetta, notorious for

its sexual bars and joints, known to the sailors as the Gut. Four

of us explored it but found no unusual

activity. We sat in rather a nice bar, drinking some kind of coloured

water, when I was approached by a raven haired beauty. She seemed quite

friendly and spoke good English. Everything was fine until she put her

hand on my knee and slid it up the leg of my shorts. I stood up, shouted for my mam and beat a hasty retreat.

We set off for Gibraltar in calm waters but

found our LCG was veering slightly to the right. The problem was corrected

by adjusting the speed of the port and starboard engines to compensate. It

was possible that the near miss with a bomb in Sicily had affected the

steering mechanism in some way. On arrival in Gibraltar we had the luxury

of eating bread again and cooking fresh food when the galley stove

performed well enough but never hot enough to cook chips. We bought beer and fresh fruit and, just before

we departed, I bought a couple of

bunches of bananas, something the folks back home hadn’t seen since the

beginning of the war. The shopkeeper advised

hanging up the green bananas in a straw shopping bag to allow them to ripen in

time for our arrival in the UK.

We set off across the Bay of Biscay and one

morning I was on the lookout on the dawn watch, which started at 4 am. As

was typical of Biscay, the sea blew up rough making it difficult to hold

our course. Then calamity struck as the engines broke down and we were

fighting desperately to keep square bow into the weather. If we were to be

hit broadside on by the large waves, we would have turned over. We took up

position on the starboard side in the lee of the bridge ready to abandon

ship if necessary. Our life belts were inflated and our shoes untied,

ready to kick them off if we had to swim for it. After what seemed like an

age, the engines started up and a cheer went up as the danger passed. The

motor mechanic had found a broken fuel pipe and fixed it with a piece of

hose and jubilee clips. Nobody thought to give the mechanic a medal for

saving us all, which is what he certainly did. We struggled on to Cardiff

for much needed repairs.

We were allowed ashore and, unsurprisingly,

our first stop was a pub and the second was a chip shop. We hadn’t had

fish and chips since we left Falmouth to go out to the Med and enjoyed

them greatly. The next morning, I posted the bananas and the presents I

had bought for the family. I believe the kids back home couldn’t remember

seeing a banana. The receipt of the parcel let them know we were back home

but, since we could not say anything about the operations we had been on,

they could only guess where the bananas had come from. Repairs completed,

we sailed north to Glasgow but, still having difficulty steering a straight

course, we ran aground.

The square shaped bow and flat bottom of our

LCG enabled us to beach where other vessels couldn't reach. A tug came to

our rescue, whose skipper was a Glaswegian, about five feet tall, with a

wrinkled, weather-beaten face and a short-stemmed clay pipe, the bowl of

which just clearing his nose. Having towed us off, he came on board and

was curious to know how we managed to run aground. We fixed him up with a

cupful of rum, by which time he better understood the unusual design and sailing

characteristics of our craft. He couldn’t believe that we'd been through

the Atlantic and wondered how the hell we kept afloat!

Eventually,

we arrived in Glasgow where it was cold and wet. A complete

refit of our craft was required, which meant we were there for some time. Our flotilla office ashore

was in Buchanan Street, up a couple of flights of stairs, over the top of

a tailor’s shop. Our LCG was placed in a Govan dry dock and with

Christmas approaching we were granted leave. Half the ship’s company

was to get Christmas at home, the other half was to get New Year’s Day at

home. I was unlucky enough to stay in Govan for Christmas and home for New

Year’s Day. Christmas would have been better at home and New Year better

in Glasgow but that was the luck of the draw. The mess caterer procured a

turkey and the usual Christmas trimmings. Eventually,

we arrived in Glasgow where it was cold and wet. A complete

refit of our craft was required, which meant we were there for some time. Our flotilla office ashore

was in Buchanan Street, up a couple of flights of stairs, over the top of

a tailor’s shop. Our LCG was placed in a Govan dry dock and with

Christmas approaching we were granted leave. Half the ship’s company

was to get Christmas at home, the other half was to get New Year’s Day at

home. I was unlucky enough to stay in Govan for Christmas and home for New

Year’s Day. Christmas would have been better at home and New Year better

in Glasgow but that was the luck of the draw. The mess caterer procured a

turkey and the usual Christmas trimmings.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

A few days before Christmas, a gang of women

cleaners came on board to clear up after the refit, each carrying a clean

and empty bucket and mop. When they had finished, the buckets were clean and

full... and we were minus our turkey and Christmas dinner! We made do with

corned meat and dehydrated potatoes. Nevertheless, my home leave at New

Year was more enjoyable.

During that leave, Marie and I discussed

marriage plans. I also learnt that the presents I had sent home were very

poor quality and not as described in the Gibraltar shop. The gold began to

come off the cross and chain, leaving a green ring around my mother’s neck.

Also, when the leather handbag got wet, the cardboard started to separate

and the lovely pattern began to peel off. I couldn’t take them back, of

course, but it taught me never to accept anything at face value again.

Back in Govan

rumours abounded about razor gangs and bike chain gangs roaming about

mugging people. Taking no chances, we went ashore in gangs of our own and

would meet in a Navy club near Central Station to go back to the ship. The

club had all sorts of amenities including a blackboard in the foyer with

notices for dances, parties or shows. If you put your name down, you would

be picked up by girls or families and taken out for the evening. It was

there that our “bunting tosser” signalman, Johnny, came into his own and

met the love of his life. There was even talk of an engagement. It was

only talk, since he was already married but, nonetheless, the family car of

his conquest regularly picked him up and brought him back.

One evening, a gang of us investigated an

intriguing building, the entrance to which was up some steps to a huge

front door. It turned out to be a kind of cheap hotel where a bed for the

night cost only sixpence. We booked on the spot and after a night out in

Glasgow returned to the hostel in Govan by train. We were shown into a

canteen with scrubbed wooden top tables, where a supper of two thick slices

of bread, sausage and a cup of cocoa was served. Heaven!

“What room are we in?”, we asked, “Oh, you

don’t have a room. All the beds are in one big room.” It was the size of a

big dance hall. Some beds were occupied by old men, sitting up and wearing

flat caps. My bed was near a pillar bearing a huge poster with a large

magnified image entitled “The Common Head Louse.” I had seen plenty when I

worked in the lab at Pompey Barracks. Nevertheless, I had a good night's

sleep and the bed was spotlessly clean. In the morning, I awoke to a

procession of these old men in long night shirts, still wearing their flat

caps and carrying a chamber pot each. “Do you want some breakfast lads?”,

one of the chaps in charge asked. We sat at the wooden topped tables, where

bacon, powdered egg and a huge mug of tea were served. When we left in the

morning daylight, we could see it was a Salvation Army Hostel!

Our LCG was moved from Govan to another area

much nearer the city centre, where we stayed for about a month. We had now

been modernised and had a couple of stainless steel wash basins in the fo’c’sle, although we still had to hand pump water from amidships and carry

jugs of hot water from the stove. During this time, I was granted home

leave over a couple of weekends, when Marie and I decided to get married.

It was difficult to arrange a wedding with all the war time restrictions

but, with the granting of compassionate leave, we married on the 8th

February 1944. Our LCG was moved from Govan to another area

much nearer the city centre, where we stayed for about a month. We had now

been modernised and had a couple of stainless steel wash basins in the fo’c’sle, although we still had to hand pump water from amidships and carry

jugs of hot water from the stove. During this time, I was granted home

leave over a couple of weekends, when Marie and I decided to get married.

It was difficult to arrange a wedding with all the war time restrictions

but, with the granting of compassionate leave, we married on the 8th

February 1944.

[Photo; Marie & I engaged].

At the end of my leave, I was expected to rejoin my ship before midnight

but, since it was already midnight when I left Warrington, I arrived in

Glasgow Central train station at about five or six in the morning. The

Salvation Army gave me breakfast, then, a tram ride to Govan docks to

rejoin my ship, but it was nowhere to be seen. I made haste for the

Flotilla Office in Buchanan Street, where I was greeted by an agitated

Petty Officer, who recognised me from the Red Cross badge on my arm.

Intriguingly, he instructed me to hide in a small office and promised he

would be back to me. I was fearing the worst, but when he returned he

apologised for not sending me a telegram a few days earlier to recall me

early from my leave. There was no mention of being adrift for several

hours so, with a sigh of relief, I told him not to worry.

After a search around the Clyde's sea lochs,

I spotted my LCG in Holy Loch. Back on board, I reported to the Skipper,

who greeted me with “Where the hell have you been?”. I elected not to

mention my late return, only that I had reported to the Flotilla office

to learn that they had forgotten to recall me. I gave each of the three

officers a piece of wedding cake and shared a glass of whisky with them.

They gave me their best wishes for a long and happy marriage. Then down to

the mess deck for some serious rum drinking with the lads.

Preparation for D Day

In retrospect, this was the beginning of our

preparations for D Day, but of course we didn't know any detail then. We

sailed up the west coast of Scotland in two lines of ten craft. The galley

stove would not light up, so obtained permission to

alter course to create a favourable wind direction to light the stove. We

were soon enveloped in a smoke cloud, which also filled the mess deck. As the cloud lifted, we received a signal,

“Are you on fire?”. We sailed round the north coast of mainland Scotland

past remote God-forsaken villages and south down the east coast, where we

practiced mock landings using live ammunition. We celebrated Palm Sunday,

1944, in Invergordon and afterwards, since all pubs were closed on

Sundays, we made do with the ship's rum.

Johnny, our Romeo, lived near Grimsby, so he decided to spend a few hours at home without permission. We

sailed and he joined us a week later. He was charged with 7 days AWOL but

it could so easily have been the much more serious charge of desertion. He

was sentenced to 2 weeks detention in cells on a supply ship. He returned

somewhat subdued but he had not done too badly. His three guards were one

short for a game of solo. Johnny obliged in return for an evening meal

and help with his daily job of 'picking' a measured weight of oakum. This

involved tearing apart a piece of rope and plucking it to form a fluffy

bunch of waste. In the old days, it was used for caulking the deck.

We docked at Southampton where large numbers

of landing craft of many types were swaying round the buoys and the place

was teaming with American GI’s. We were sorry to lose our skipper there

him being a great bloke who was very popular with everyone. His

replacement was a large, rather severe looking black bearded Lieutenant.

He had a nervous twitch in his face, which could be mistaken as a wink by

the unwary which included a Padre who was seen to wink back. His name was

Lt Commander Ring.

Sailing from Southampton to Portsmouth, we

struggled in gale force winds to maintain our heading and, as the Needles off the Isle of Wight

came ever closer, he knelt down near the voice pipe in what seemed to be

an act of pray. The craft slowly swung away from

danger until we were back on course. In Portsmouth, the situation was much

the same as Southampton - lots of landing craft, activity and Yanks. We

loaded up with stores, water, fuel and ammunition. The food was in boxes

with rations for four men in each box. These were known as compo rations -

typically tins of soya links (sausages), tins of herrings in tomatoes, a

tinned pudding, a block of chocolate, chewing gum and toilet paper. You

didn’t know what you’d got until you opened the box. Usually, quite a lot

of boiled sweets and, of course, hard tack biscuits. It was Sunday, June

4th. The coxswain went ashore and come back with the Sunday papers.

I asked the Skipper for permission to take

the RC party ashore. It was only a short distance up Queen Street to the

Catholic Cathedral. The Skipper’s reply, “Permission not granted”. I

replied with a question, “Why can’t the church party go ashore? The

coxswain has already been.” His face turned from red to purple. “We are

now under sealed orders and if I say you’re not going, you bloody well

stay.”

All hands fell in for the Sunday religious

service and no one was excused. The Skipper took command of the occasion,

which included an inspection and prayers. The service was Church of

England and in those days Roman Catholics, like myself, were not allowed

to attend. I waited for the order, “Fall out RCs.” but none came, so RCs

were obliged to stay. After Divisions, I complained to the Skipper, who

apologised profusely, assuring me he had simply forgotten to give the order

for us to fall out. It was an understandable mistake, since we were about

to set sail for the beaches of Normandy

and he had a lot on his mind.

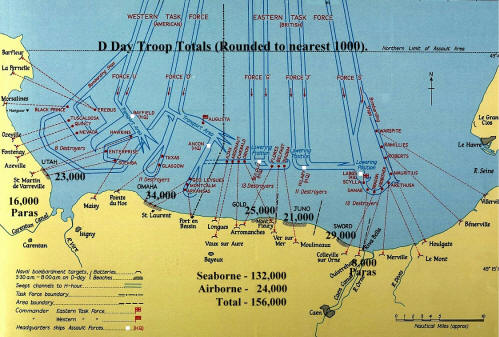

We dropped anchor off the Isle of Wight in

our designated place as part of the largest amphibious invasion force in

human history. The Skipper had read his sealed orders and informed us we

were sailing that night to take part in a major landing. We were to give

support to a landing, code name Sword. We would be on the extreme left

flank, our destination was Ouistreham in Normandy. If we sank, any

survivors were to swim to the right, as the left would be enemy occupied.

In the event, the invasion was postponed by 24 hours due to bad weather.

On board, there were mixed feelings of excitement, apprehension and sheer

terror. We sailed the following night and were to strike at dawn on the

6th June 1944 – D-day.

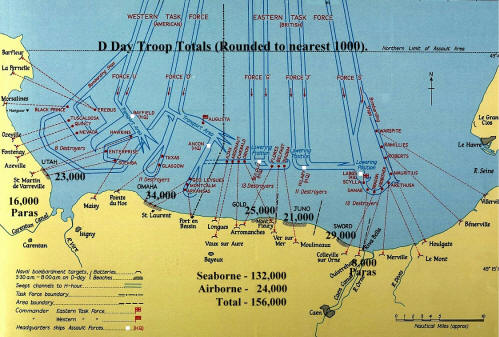

D Day

The weather wasn’t too bad as we set off across the Channel at the head of

the armada of ships and landing craft of every description heading for

Sword beach - a situation repeated on the other four landing beaches.

There were few ships to our portside, because we were on the extreme left

flank and all the while, overhead, there was a constant drone of aircraft

engines.

As dawn broke, I could see the beach in the

distance. There was a line of gunboats (LCGs), rocket ships (LCRs) and

flack craft (LCFs) and, at the appointed time, all hell broke loose. We

were shelling open targets and the rocket ships were firing salvos of 24

rockets at a time in quick succession. Nearby, converted landing craft

carrying machine guns, mortars and smoke generators unleashed their awesome,

destructive power. Job done, we circled back to make way for the tank

landing craft to unload their tanks and the landing craft personnel to

discharge their troops onto the defended beaches.

We then stood by, waiting for the Forward

Observation Officer to select targets for us. Meanwhile, I could see tanks

and men making their way up the beaches, while flail tanks thrashed the

beach ahead of them with revolving chains to explode concealed land mines.

Behind them, other specialised tanks laid out mesh carpets for the cars,

trucks and lorries to drive safely across the sandy beach with their

supplies.

Gradually, as the beach heads were forming,

troops and vehicles gathered in a secure area ready for the push inland

but there were many casualties. After the initial shock of the landing,

the defending Germans opened fire with renewed vigour. Overhead, we heard

the whine of shells from our destroyers, battleships and cruisers. They

were hitting targets inland, to ‘soften’ things up before the assault

troops pushed through the beaches to form secure bridge heads inland. The

hard pressed beach masters were preparing the tanks and lorries to move

off the beach in an orderly fashion to finally secure the beachhead. With

the visible beach area now filled with our own troops, our next targets

were inland, which were identified by a Forward Observation Officer, who

was close to the front line.

There were dead bodies floating in the

water, which made me feel sad but lucky to have survived the day. We had

been hit seven times, with no casualties, by non-explosive, armour

piercing shells. One was found in an empty cordite locker on the deck and

another in a box of soap in the storeroom. One penetrated the hull just

aft of the engine room, where a row of emergency lamps, being charged up

from the generator in the engine room, had been put out of action. We were

lucky to avoid casualties. If the cordite charges had been in the locker

when the shell pierced through, it would have been a very different story.

We remained at action stations and I busied

myself acting as chief cook and bottle washer, since there was no medical

related work for me to do. I also provided the gun crews with improvised

cotton wool ear protectors and invented the world’s first tea bag when, to

prevent tea leaves floating around my brew, I made tea bags from my

medical kit gauze. It worked a treat and I could reuse the bags to make a

fresh brew a little stronger if required.

By midnight, we were no longer on full

alert, allowing the gun crews to remove empty shell cases and to prepare

ammunition ready to fire whenever required. None of us slept with the

sounds and sights of total war all around us - explosions, white flashes,

lines of tracer bullets and shrapnel falling all around us. A couple of

tots of rum helped calm our nerves. What a shock it must have been for the

German soldiers on duty in their concrete bunkers, overlooking the

beaches, to see the largest amphibious invasion force in history coming

towards them, when such duty had been previously so uneventful. I imagined

their frantic calls to disbelieving senior officers. We didn’t

realise we were making history after our disastrous retreat at Dunkirk

four years before.

On the morning of the 7th June, we resumed

firing, taking orders from the FOOs at the front. The nervous

excitement was palpable but we soon settled down to a routine - one gun

crew closed down another on standby duties.

The Germans deployed small speedboats

carrying high explosives. Their two man crews set the boats on auto-pilot

as they approached their target before launching their rubber dinghy to

save their lives and to give themselves up. The speedboats were difficult

to see in the dark but they had a red pilot light on their stern. Orders

were to fire at any red light moving in the water, which was concerning

since our inflatable life belts were also fitted with red lights.

After the third night, I accompanied an AB

to a nearby destroyer for a medical examination after he fell asleep while on duty, even while standing up. On board the

destroyer, I outlined the case to the Medical Officer, explaining that the

AB hadn't slept for three days, was not normally quick witted and that we should be lenient towards him. The doctor was a Scot, I was a

Lancastrian and the patient was a Cockney. I could just about

understand both of them so I acted as interpreter between the Scot and the

Cockney. I'm sure the doctor was glad to see the back of us as he gave me

a note and prescription that meant the AB would not be charged. The pills

were caffeine, a mild stimulant, which became known as his keep-awake

pills. He reported to me regularly over some days to receive his

medication.

We came under accurate fire from a heavy gun

positioned on a hill some distance to the east, which gave cause for

concern. The buzz was that the enemy were laying mines at night and their gunfire was designed to drive us into them. The LCGs took turns to

shell the gun emplacement and when it was our turn, we sailed east, fired

off our shells and apparently silenced it... until we turned about towards our makeshift harbour when shells

fell all around us. We survived without taking a hit but these were

anxious moments.

Some beached merchant ships on our port side

formed a breakwater or makeshift harbour. Two of our lads spoke to the Polish skipper

of one of these ships who threw them a line and invited them

on board. He spoke good English and invited them to salvage anything from

the cargo which was under water. They recovered three wooden crates and

rowed back to our craft with their booty. Each crate contained

demijohns of rum, which was soon bottled by us and sampled just before the Skipper found

out and promptly confiscated it. However, he agreed to splice the mainbrace,

effectively doubling our rum rations while stocks lasted. The bulk of the

bottles were locked in the rum store, while a few were dangled over the side for

emergencies!

A gale blew up causing our anchor to drag so

we sought refuge from a nearby

cruiser,

HMS Dane. As we drew closer, they fired a line for us to tie up

alongside. It was a difficult manoeuvre as our craft steered into a

heavy sea, floundering about and being pushed away. We turned about

and attempted to close in but the lines were still falling short. Even in

the calmer waters of Scottish lochs a good number of jetties bore the

physical scars of our manoeuvring difficulties. We edged closer and closer then, inevitably,

too close and we rammed the side of the cruiser, causing a six-foot,

three-cornered tear in her side. As we tied up, lots of gold braided

officers peered down on us. They were amazed that a fiddling little craft

(I think the word was fiddling - anyway it began with the letter F) could

cause so much damage. While their damage control crew patched up the side

with timber, we took the opportunity to cadge some bread from them. As the

weather calmed, we went back to our makeshift harbour and I believe HMS

Dane returned to Portsmouth for repairs.

Next morning, we gazed upon a silver sea of

herring, stunned by some underwater explosion. We tied lines to buckets and

reaped the rich harvest. The fish wriggled as we gutted them and we all

enjoyed hearty meals of fish with our newly acquired bread.

Our Luck Ran Out Our Luck Ran Out

Sword beach was secured and the army was pushing towards Caen. Supplies

and reinforcements were arriving unhindered, apart from occasional air

raids, which were dealt with by the RAF. Our job was exclusively to

support our advancing army by firing on targets as they were identified. About

two weeks after D-day, on a quiet, sunny afternoon, we lay at anchor with

very little to do.

[Map courtesy of Google Map Data 2017].

Able Seaman Lodwidge was on Quartermaster duty on the

bridge near the Oerlikon gun. He spotted a hit and run raider flying

towards us. He only had time to put one shoulder under the holster

before firing in the general direction of the plane, hitting it in the

tail and bringing it down into the sea. The regular ack ack gunner was

off duty at the time and on his return he painted a swastika on the gun

shield and wrote JU88, thereby claiming a Junkers 88 for his gun.

A couple of days later, we sailed along the

coast to fire on targets identified by the Forward Observation Officer. It

was a lovely sunny afternoon and the German heavy gun on the hill was

strangely silent. With little activity, one gun crew went below for tea, while the other stayed on station by their gun. The

Marine Officer wanted to see his batman, a nineteen-year-old I knew as Slinger Woods, but he was having none of it; “Bugger him, I’m going for my

tea”. As our craft turned about for our anchorage, the ship shook and a hot blast of air

from an explosion below deck hit me, followed by a pall of smoke from

the hatch near the ammunition room. We had been hit by a six inch shell

from the gun on the hill.

It had exploded in the Marine Mess Deck

where fourteen lads had just gone for tea, including Slinger Woods. There

was a considerable amount of panic as the Marine Mess Deck filled with smoke

and the first casualty climbed out on his own and made his way aft to the

wheelhouse, which served as my sick bay. The

standby gun crew helped other wounded to the wheelhouse, the first of whom

had a hole in the side of his neck, which I filled with sulphanilamide

powder before applying a field dressing. I left one of my helpers to dress

various shrapnel wounds when a good friend of mine, Marine Peter Rabbit,

was laid down on the deck of the skipper's cabin. He had a large sucking

wound in his chest and a lot of shrapnel wounds about his upper body and

arms. I did what I could for him including a shot of

morphine from a syringe containing a standard dose.

Another marine was laid on the deck in the

small galley, across from the Skipper’s cabin. He had a hole in one of his

arms and a piece of shrapnel had broken both bones in his forearm. I dressed

the wound, splintered his arm and left Jimmy the One to dress any other

wounds, while I attended a corporal Marine, who was lying on the

quarterdeck with a large hole through both his ankles. I dressed them both

but he was still bleeding badly so I applied a tourniquet to both legs.

The 1st Lt was trying to administer a shot of morphine to another casualty

but could not penetrate his skin in the cramped conditions. In this emergency situation, I took the

syringe and pushed him out of my way, causing him to overbalanced

backwards into a roasting tin of soused herring,

which had been left on the galley floor.

When the remaining wounded were attend to,

making a total of seven, I checked the Marines mess deck for the remaining

seven known to have been in the room. It was a

terrible scene of total carnage with 6 to 9 inches of water and blood

on the deck and body parts strewn everywhere. There was no doubt that the

missing seven were all dead, including Slinger Woods. One marine

was still holding a bread knife in his hand.

Mercifully, they all died instantly.

I strapped up the wounded in Neil Robinson

stretchers and lined them up on deck as we came alongside a merchant ship

with an emergency hospital. I accompanied them on board. I looked nothing

like a Sick Berth Attendant, since my singlet and arms were smeared with

blood and my hair was a tousled mess.

I led a RC chaplain

to Peter Rabbit, who was lying on an examination couch. He was barely

conscious, while the chaplain performed the Last Rites over him. We were

ferried back to our craft, together with a Church of England chaplain, the

RC chaplain and a volunteer party of men, who came to prepare our dead for

burial at sea. They did their best to sort out various body parts, tied

them in hessian sacks and laid them inside a hammock, one for each body,

using shells to weigh them down. They were then laid on boards for the

burial ceremony, which was attended by the whole ship’s company and then

committed to the deep as the boards were tilted and they slipped off to

their final resting places. When the chaplains and visitors had gone, we

were left alone in a rather sombre atmosphere. I felt empty and sad. The

Skipper gave me a full cup of rum and I dozed off into a rather uneasy

sleep. The next morning, I cleaned myself up as best I could, as my kit was

incomplete and severely damaged. By this time, my right knee was aching

and had become swollen.

One of the lads rowed me across to a

destroyer to see a doctor, who padded the back of my knee with cotton wool

and put a splint on. This gave me a bent right leg and the ability to walk

on my toes. He also treated our mascot dog, Butch, by removing a piece of shrapnel

from a paw and bandaging it up. The mood on board was sombre, everyone

doing his best

to remain composed. The tall lad, who had pulled the chicken’s head off in

North Africa, was curled up in a ball with a silly grin on his face. I was

quite shaken and found myself often unable to complete a sentence, an

affliction I was quite conscious of but managed to overcome in time.

The day after the funeral, we headed for

Southampton and eventually tied up to a tree on a river in Lord Beaulieu’s estate. Most of us were dressed

in odd items of uniform and must have looked a sorry sight. Our ship was

due to have repairs in Southampton, so the Skipper granted us a spell of

home leave. Before I left the Skipper, who was busy notifying the next of

kin, agreed that I should visit Peter Rabbit's family to tell them of his

injuries. They lived at Leigh, quite near my home town.

On the Underground between Waterloo and

Euston, the carriages were full, so I stood on one leg. A woman

nudged her husband and said, “Get up and let that wounded sailor sit

down.” I didn’t realise how bad I looked! I arrived safely in Warrington,

where Marie and I lived with her mother. There was no bathroom, so I

enjoyed a good soak in the Corporation Baths in Legh Street and a change

of clothes comprising a clean white shirt and my best uniform (Number

Ones), the uniform I was married in and considered too good to keep on

board the landing craft. Marie and I caught a bus to Leigh the next day to

visit Peter's family. They were very surprised to see us and made us very

welcome. There was Peter’s mum and dad and I think a couple of brothers

and a sister. I waited a while before I told them the purpose of our

visit. Peter’s elder sister was a nursing sister in the Warrington

Infirmary, quite near to Froghall Lane, where we were living. Being a

nurse, I described the extent of Peter’s injuries and left her to explain

to her folks what they wanted to know. They were comforted to know that I

had seen him receive the last sacraments. It was a difficult visit to make

but I felt much better afterwards but just two days later, Peter’s sister

told us that he had died and had been buried at sea.

My knee

was improving by the day, although the noise of trains passing by on the

main Liverpool to Manchester railway line, which was quite close to Froghall Lane,

often caused me to wake in a cold sweat, thinking we were being attacked.

Eventually, I got over it. My leave was extended, because

dockyard workers refused to enter the Marine’s mess deck, where the shell

had exploded killing the 7 men. I believe an

increase in pay and a deadline for the repairs resolved the impasse.

The craft had been refitted and the crew

given new kit. My pride and joy was a large green suitcase that I kept for

many years. We, the naval ratings, were also issued with khaki battle

dress and army type boots and looked like Commandos with the Combined

Operations badge and a Royal Navy flash on the top of each arm. Back on

board, the fresh water was found to be tainted and shrapnel holes in the

Marine’s mess deck, which had allowed contaminated liquid to seep into the

fresh water tank, were repaired, the tanks flushed out and refilled with

fresh water.

In all, we were in Southampton for a month

and after a few trials on the refitted craft, we sailed to Portsmouth,

where we spent the next few months beached with our nose on a prepared

area known as a hard. In September, the Germans launched their second

secret V2 rockets from somewhere in Holland. Because of their high

velocity, there was no warning of these attacks. Most of the rockets

landed in the London area, literally out of the blue. We never did return

to Holland and by the end of October rumours started to circulate of

another operation.

Operation

Infatuate - Walcheren. Operation

Infatuate - Walcheren.

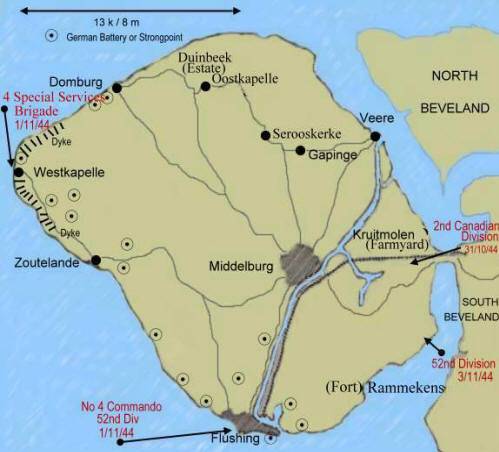

There was a strong buzz on the mess deck

that we were moving to Southend and a couple of the lads who lived in the

area were excited at the prospect of seeing their families. However, their

hopes were dashed when we arrived in Ostend.

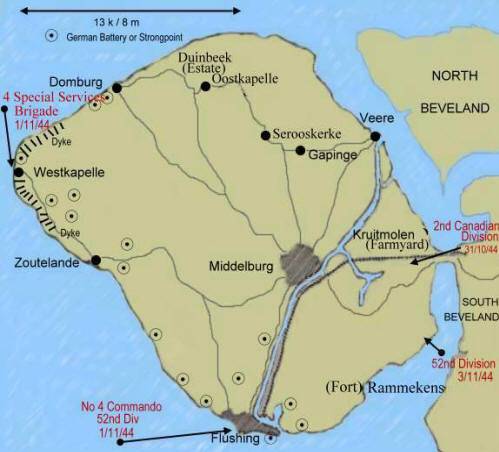

It soon became an open secret that our final

destination was the heavily defended island of Walcheren in the mouth of

the River Scheldt at a place called Westkapelle. The port of Antwerp was

in Allied hands but could not be used by Allied supply ships because of the

enemy's big guns denying access.

Ostend was badly damaged, including the

dockyard and the locals were just getting used to the idea of living again

after the German occupation.

Operation “Infatuate” got underway on November

1st, the aim of which was to capture Walcheren Island and thereby open up

Antwerp to the sea. As we moved out of Ostend, about six minesweepers led the

convoy but at least two of them were blown up by mines.

The dawn was very grey and damp. We could see a

lighthouse still standing after earlier bombing raids had breached the sea wall

causing flooding in land.

Bad weather prevented the planned RAF's softening up attack and, as all planes

were grounded, the bombarding battleships had no spotting planes and there was

no air support for the landing craft. land.

Bad weather prevented the planned RAF's softening up attack and, as all planes

were grounded, the bombarding battleships had no spotting planes and there was

no air support for the landing craft.

At about 8am, a motor launch put down marker

buoys. It was fast and manoeuvrable and avoided heavy fire from the

Germans. The three big warships opened fire without reply from the German

battery and soon a heavy smoke screen laid by the Germans blotted

everything out; we could no longer see the lighthouse.

[Photo; RAF Bomber Command Walcheren showing a major

breach in the dyke with flooding in the hinterland. © IWM (C

4673)].

The LCGs and the rocket ships engaged the

shore batteries and all hell let loose. It seemed as though the water had

been marked out in squares by the enemy gunners and once a vessel entered

a square it became a sitting target. It seemed our skipper was steering

along the lines, since we were not hit.

The rocket ship opened fire but a lot of

rockets dropped short and hit our own craft. We pulled out. I was on the

quarterdeck and could see the beach getting further away when, just as I

was thinking thank God for that, we turned about and went back in again.

Once more the skipper found the lines and avoided the squares. There were

craft blowing up all around us but we emerged unscathed. We fired our 4.7

inch guns at anything we could.

There was a new type of gunboat being used,

more like a ship than our coffin shaped barges - I think they were

petrol-driven, being much faster and manouverable. They had ballast tanks

that could be flooded, largely removing the effect of waves and giving

them the characteristics of a beach fort. I saw one of them get hit. One

second it was there, then a huge white flash lit the sky and the next

second it was gone. I saw another of the new gunboats beached with Germans

on deck with flame throwers toasting everything in their way.

On the return to Ostend, we learned losses of

around 75% of men and ships had been incurred. When the weather cleared,

rocket firing Typhoon planes went into action and the guns of Walcheren

were finally silenced. A fleet of minesweepers cleared the estuary and

supply ships were soon docking in Antwerp. I had a copy of a signal sent

to the craft. It read something like, “You were the men who turned the key

to open the lock to Antwerp”, signed Mountbatten.

[For the part played by the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry

Division and other land forces in this operation,

please click here]. On the return to Ostend, we learned losses of

around 75% of men and ships had been incurred. When the weather cleared,

rocket firing Typhoon planes went into action and the guns of Walcheren

were finally silenced. A fleet of minesweepers cleared the estuary and

supply ships were soon docking in Antwerp. I had a copy of a signal sent

to the craft. It read something like, “You were the men who turned the key

to open the lock to Antwerp”, signed Mountbatten.

[For the part played by the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry

Division and other land forces in this operation,

please click here].

Soon after, we returned to Portsmouth in the

teeth of gale force conditions. I saw a tower just past Dover but with

both engines going full ahead we weren’t making much headway. When the

weather calmed one of the LCTs had broken in half, the after part being

taken in tow with the crew still on board. We later tied up in Portsmouth

dockyard.

The whole Ship's Company was placed on

parade in the dockyard, because King George VI was to pay us a visit. We

stood there for a couple of hours in our summer uniform awaiting his

arrival. It was a bitterly cold mid November day but overcoats were not to

be worn. We were brought to attention, as he walked right past us. One of

the officers was heard to tell him, “These are some of the men who took

part in the Walcheren landing.” His reply, “Are they back already?”, seemed

to lack any real understanding of what we had been through and what we had

achieved. We decided that an extra tot of rum would warm us up when we got

back on board. We toasted the Kings health, albeit reluctantly.

From War to Peace

We were given leave when I learned that

Marie was 2 months pregnant. Back in Portsmouth there was little useful

work to keep us occupied. All-night leave was commonplace. While standing

at a bar, I was joined by a tall corporal marine, a Preston lad. He warmly

greeted me, “Hello doc’, thank you for saving my life.” It was the marine

who had a hole in each ankle and I had applied a tourniquet. He was now

fit for duty. As a matter of fact, two or three of my wounded rejoined the

ship.

The mess caterer on board had procured a

large turkey for Christmas dinner. Our roasting tin wasn't big enough to

cook it in but we eventually borrowed one from a cookhouse near Nelson’s

Victory but it was too big for our oven. Not to be defeated by this

setback, the motor mechanic built an extension for the oven but generating

enough heat to cook it was challenging. The 'cook' sat up with it all

night keeping the fire going, while basting the bird. In the morning, he

emerged from the galley with his face quite black apart from two white

circles around his eyes and one around his lips.

Traditionally the officers wait on the

ratings at Christmas dinner. The youngest marine went into Jimmy the One’s

cabin and came out wearing a sub-lieutenants uniform. After dinner, he

handed round a large box of cigars, which we later discovered belonged to